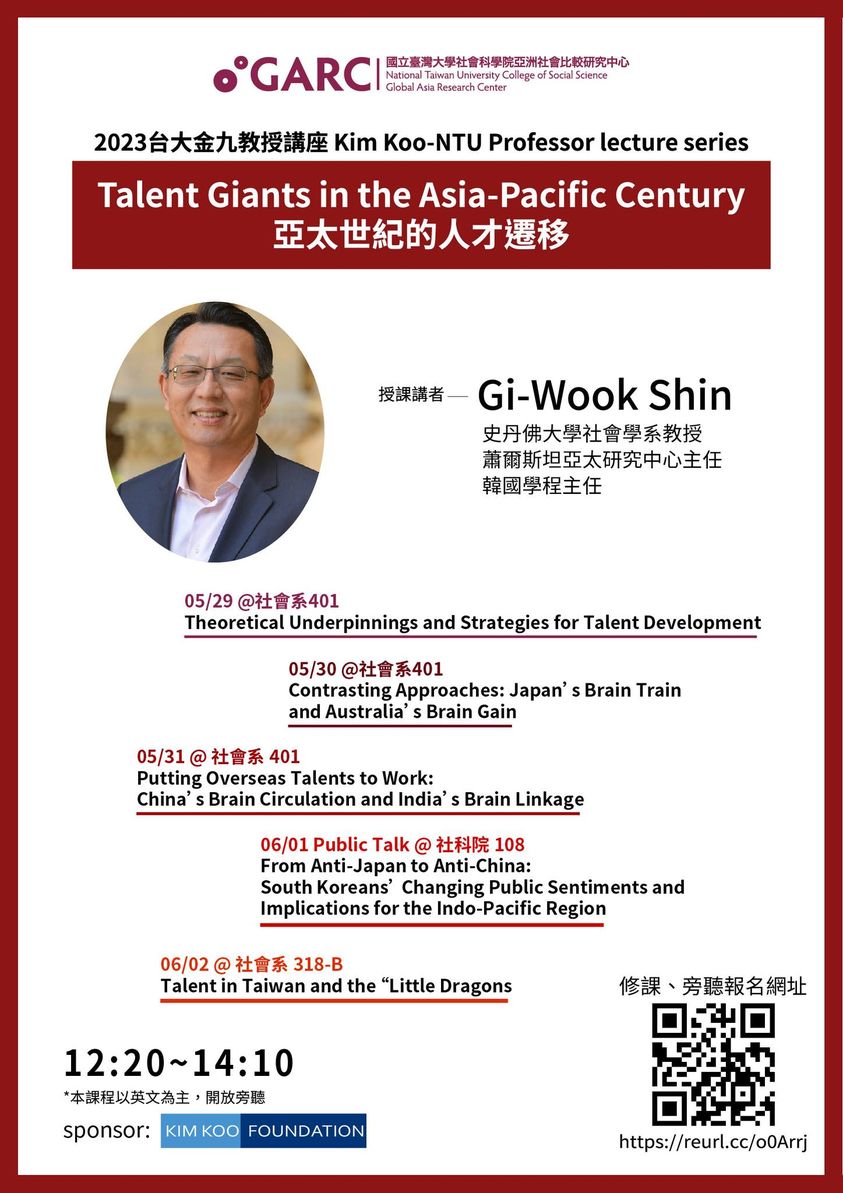

About the Lecture Series

Professor Gi-Wook SHIN from Stanford University presented his latest research during the week-long Gi- Kim Koo-NTU Professor Lecture Series. His research offered new explanations for the rapid post-war development of Asia-Pacific countries by focusing on how these countries train, recruit, retain, and utilize high-skilled nationals and non-nationals, i.e. talents. He argued that human resources were key to national development, though countries differed in their talent management and development strategies. He examined talent migration through higher education and migration policies in Asia-Pacific, classifying talent migration into three categories: foreign talent importation (crucial for Australia and Singapore), policy borrowing (vital for South Korea, China, and Taiwan), and contributions from diaspora communities (represented by India and the Philippines). His comparative research sought to explain the varied talent management strategies and their impacts across different countries.

In the first lecture, redefined the concept of “talent,” dividing it into human capital and social capital, which were equally important in the knowledge economy. He further grouped talents into three geographical categories and ethnic backgrounds: domestic, foreign, and diaspora. He argued that talents should be considered both as “stock” and “flow.” Countries had to adjust their talent management strategies to minimize risk or maximize returns for better economic and social development.

In the subsequent lectures, he analyzed and compared the talent management strategies of major Asian countries and their implications. The talent management strategies employed by Japan and Australia represents two distinctive models. Japan focuses on “talent training,” whilst Australia emphasizes “talent acquisition.” Japan’s policy emphasizes home-based yet world-class training. Japan’s status as one of the few advanced Asian economies is the result of its comprehensive domestic talent training system, which has produced high-caliber scientists and engineers. However, Japan’s talent training strategy has its limitations, including a rigid, male-dominated corporate training system and a lack of multicultural competencies needed in the global knowledge economy. Australia, with its vast land and sparse population, has always needed human resources. However, from the early 20th century until the 1970s, Australia had a “White Australia” policy. It wasn’t until 1978 that Australia adopted multiculturalism, allowing many skilled immigrants to gain permanent residency. The government attracted international students through higher education, making it easier for them to stay and work in Australia through a points-based immigration system. Australia also has built social capital and networks through alumni with Australian experience. However, it also faced polices challenges, including anti-immigrant sentiments, political tensions with China, and COVID-19-induced skill shortages. Through the examples of Japan and Australia, Professor Shin showed how different policy contexts and national development trajectories, with changing times and international economics, prompted countries to adjust their policies to manage talent flows.

China and India, as emerging powers, utilized talent circulation and linkage strategies to achieve economic development. Since the early 21st century, a large number of Chinese students have pursued higher education abroad. With the domestic labor market needing skilled workers and overseas markets unable to accommodate them, this led to a reversal of the brain drain, contributing significantly to China’s development through technology transfer, higher education enhancement, and the introduction of R&D and entrepreneurial talents. National programs like the Changjiang Scholars Program and the Thousand Talents Plan played key roles in attracting returnees. However, these strategies were not without their challenges. The contributions of short-term academic exchanges were questioned and geopolitical risks posed significant uncertainties.

India, with its long colonial history and extensive migration experience, adopted a vastly different talent strategy, primarily through talent linkage. The dispersed Indian diaspora spontaneously connected across countries, providing the necessary information, networks, and even funding for the domestic and international migration of Indian talents. These Indian diaspora communities could effectively convert social capital into human capital mainly because the overseas communities maintained a strong cultural identity. In addition, Indian government’s relatively lenient regulations supported the recognition of overseas Indians’ identity and turned them as workforce reserve that could be utilized when needed.

In this system, state-centered talent programs seem to be absent, yet India’s industries and technology continue to develop. Returnees maintain connections with their previous host countries, facilitating continuous talent circulation and linkage, allowing Indian talents to flow both domestically and internationally. However, this talent linkage mainly benefits the middle and upper classes, and India’s entrenched caste system reinforces class and sub-group distinctions, potentially weakening cross-national connections.

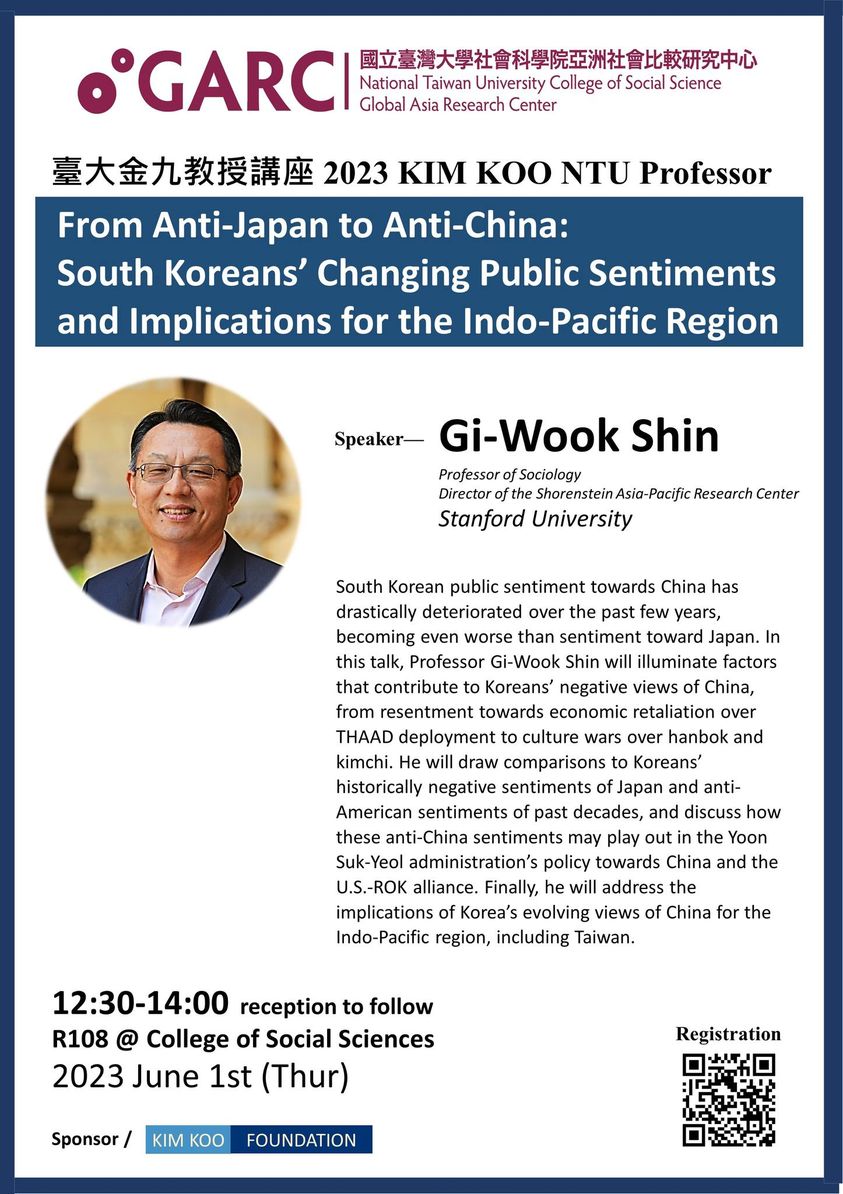

In his public talk held on June 1st, Professor Shin explained and analyzed why South Koreans shifted their collective sentiment from anti-Japanese to anti-Chinese. He concluded his lectures by exploring areas where Japan, Australia, China, and India could learn from each other and potential future directions and by summarizing the theoretical implications and policy significance of his analytical framework. Professor Shin’s insightful lectures inspired numerous interesting questions and discussions about Asian talent migration and management.

Professor Shin’s public talk “From Anti-Japan to Anti-China: South Korean’s Changing Public Sentiments and Implications for the Indo-Pacific Region” can be accessed https://speech.ntu.edu.tw/ntuspeech/Video/id-3608

Note taken by Ting-She Chang, Chih-Heng Su, translated by Ying Tsen CHEN, edited by Wei-Yun Chung