Transnational Families and the Second Generation in Asia

On July 19 and 20, we hosted the two-day international conference “Transnational Families and the Second Generation in Asia”, inviting 16 scholars from the United States, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Taiwan to discuss their research on inter-Asia families in this two-day conference. The conference took on a hybrid format, combining both in-person and online participation, with around 100 attendees from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Europe, and the United States. The presented papers during the conference revealed how macro-level geopolitics, ethnic relations, and societal contexts influence parenting practices’ temporal, spatial, material, and emotional frameworks. Through the lens of social welfare policies, language use, and political practices, the papers discussed how new immigrants and their children shape their identity in Asian societies. The analysis focused on how they navigate, manifest, or negotiate their identity within social constraints and opportunities, acquiring resources and constructing their citizenship in the process.

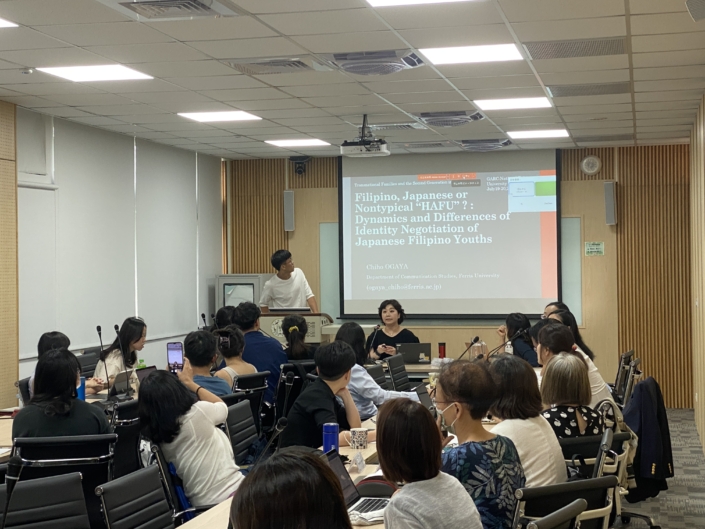

The morning sessions on July 19th unfolded the profound impact of geopolitical, ethnic relations, policy, and social contexts on the identity formation of the second-generation immigrants. Chiho Ogaya examined the distinct yet similar identity development patterns of Filipino-Japanese mixed-race adolescents who either returned to their motherland, the Philippines, with their mothers or stayed in Japan. She pointed out that different social contexts and community support influence the identity of Filipino-Japanese mixed-race children. Pei-Chia Lan’s research focused on how second-generation children in Taiwan negotiate ethnic identity labels imposed by external communities under geopolitical and social contexts, shaping or “manipulating” their identity accordingly.

Minjeong Kim and Ilju Kim shifted the discussion to how South Korean second-generation individuals perceived policies favoring them. The South Korean government introduced various policies that provided families of marriage immigrants with additional resources aiming to improve their socio-economic status and boost childbirth rates. They found that while these policies provided material advantages to the second generation, they also reminded them of their ethnic identity, which deviated from the mainstream societal expectation of “pure Koreans.”

The session in the afternoon focused on the emotional interaction and the language capital accumulated within families and communities and how they shaped adolescent immigrants’ identity. Yuk Wah Chan’s research examined how Hong Kong adolescents born to Chinese parents navigated their identity amid the intense tension between Mainland China and Hong Kong. The languages (Cantonese or Mandarin) and accents they used to interact with peers represented and constructed their personal identity, and at times further resisted stigmatization of their mainland identity.

Wai-Chi Chee explored the role of Southeast Asian adolescent immigrants in Hong Kong in the anti-ELAB movement and how their participation in these social movements shaped their Hong Kong identity. Wai-Chi Chee pointed out that although incomplete citizenship rights (more restrictions compared to Hong Kong locals) make Southeast Asian immigrants feel lacking in legitimacy to participate in social movements, some immigrants learned Hong Kong’s political system through participation in social movements, and their participation enhanced their emotional connection with and belongingness to Hong Kong. Their involvement also contributed to the acceptance of South and Southeast Asian immigrants in Hong Kong society, positively impacting their identity negotiation.

Hyun Mee Kim investigated the identity of children of Korean-Vietnamese transnational marriages who returned to Vietnam with their mothers after their parents’ divorce. These children were emotionally closer to South Korea than Vietnam due to the better economic prospects of the former. With assistance from their Vietnamese families, they learned Korean and tried to secure their South Korean residency or citizenship. Whilst such familial assistance aimed at facilitating the “return” of Korean-Vietnamese children to Korea reinforced their ties with their Vietnamese families, it also creates tensions within families.

On July 20, the focus was shifted to the parenting practices in inter-Asian families. Hsiu-Hua Shen examined how gender ideology is reinforced through parenting practice with Taiwanese businessmen’s cross-Strait families. Tuen Yi Chiu and Ruby YS Lai explored Hong Kong-China families with some family members lacking Hong Kong residency. The quarantine policies during the COVID-pandemic disrupted these cross-border families established mobility rhythm between Hong Kong and China. Their research illustrated how transnational families operated and negotiated with the state’s policy at micro, meso, and macro levels and on various spatiotemporal scales.

Jeehun Kim examined how the parenting practices of Korean mothers in American and Singaporean transnational marriages were influenced by cultural contexts i and how they shaped their children’s Korean identity. Korean mothers are known for intensive parenting. Such practices are widely accepted in Singapore, but less so in American contexts. In the American context, such parenting is considered “Asian” or “Korean, ” with rather strong negative connotation. Jeehun Kim found that the negative and non-American connotation of their parenting style caused Korean mothers to adjust their mothering practices to comply with the mainstream and further influenced their mixed children’s identity.

Hsiao-Chuan Hsia explored how Southeast Asian immigrant mothers in Taiwan regained their cultural identity through participating in political advocacy and parenting. Southeast Asian women marrying to Taiwanese men are long discriminated against by the Taiwanese society. These women empowered themselves and redefined parenting through advocating for their children’s rights. Tsung-Yi Huang investigated how Taiwanese marriage immigrants in South Korea practiced parenting in a society where mothers were expected to raise a “pure Korean” child and intensive mothering was a norm. She explored how gender, class, and nationality affected these mothers’ parenting practice, re-shaped their ethnic and national identity on their mothering practices, and influenced their interaction with their husbands and the extended families of the latter. Joycelyn Celero compared Filipino-Japanese transnational marriages between 1970 and 2000 and found that the family dynamics and parting styles of these marriages differed based on the broader regional socio-economic contexts in which these cohorts were situated. In the marriages of older generations, Filipino mothers were encouraged to learn Japanese, integrate into Japanese society, and become mothers of “Japanese” children. In contrast, younger Japanese-Filipina couples tend to prepare their children to become global citizens with higher mobility rather than merely becoming Japanese. Her research highlighted the importance of understanding the changes and continuities in transnational families and parenting practices across different generations through comparison.

Written by Chao-Kai Heu, translated by Ying Tsen CHEN

低解析度-80x80.jpg)