De-institutionalization of Asian Families

Under the waves of globalization and modernization, Asian families are undergoing dramatic transformations, challenging traditional notions and institutional frameworks of family. This conference brought together scholars from various disciplines to rethink the diverse forms and future directions of “Asian families” from interdisciplinary, comparative, and empirical perspectives. It aimed to understand further the changing landscape of intimate relationships and lifestyles in Asia, delving into the de-institutionalization trends of Asian family systems and their profound impacts on intimate relationships and daily life from the perspectives of gender, generation, migration, and policy.

Trends in Asian Family Research and De-institutionalization

In the first keynote address, Professor Sara R. Curran analyzed research literature on Asian families, gender, marriage, divorce, and cohabitation from 1996 to 2025. She noted a rapid growth in relevant East Asian research (especially China and India). However, she observed that most studies still centered on marriage, with less attention paid to divorce and cohabitation. While early research focused on traditional family issues, recent studies have shifted towards more complex topics like law, divorce, and mental health (particularly depression). Research topics also varied by region; for instance, China focused on fertility, Japan on employment, and India on violence, women’s rights, and health. Curran emphasized that future research should delve deeper into how institutionalization influences family and marriage practices in various Asian regions, interpret marriage and family concepts from an Asian perspective to avoid over-reliance on Western theoretical frameworks, and encourage cross-regional and interdisciplinary collaboration for a more comprehensive understanding of Asian families and gender issues.

Subsequent panel discussions further explored the de-institutionalization phenomenon. Professor Emiko Ochiai presented a “two-stage institutionalization and de-institutionalization” view of Asian family systems. Taking Japan as an example, she illustrated the evolution from the relatively free traditional families of the Edo period to modern families characterized by widespread marriage and fewer children after the first demographic transition, and then to the de-institutionalization of modern families as women moved beyond the housewife role during the second demographic transition. She stressed the vast diversity in traditional family systems across Asian countries and the impact of “compressed modernity,” making it difficult to apply Western two-stage modernity concepts simply. James Raymo focused on the effects of divorce, remarriage, and parenting on family inequality in Japan. He found that lower-educated women had higher divorce rates, but no significant educational differences in remarriage rates; divorced mothers spent less time interacting with their children. Notably, more highly educated mothers in Japan spent less time interacting with their children, which challenged the “diverging destinies” theory in Western contexts and highlighted the uniqueness of family changes in Japan. Professor Lake Lui, through in-depth interviews, observed a “re-institutionalization” of marriage among young people in Taiwan. Over half of the young adults viewed marriage as an essential life stage, with highly educated individuals meticulously planning marriage, career, and childbearing. Others, though not necessarily desiring marriage, entered it due to social and family pressure, adopting independent strategies within marriage or developing distinct single lifestyles emphasizing self-realization and friend support networks.

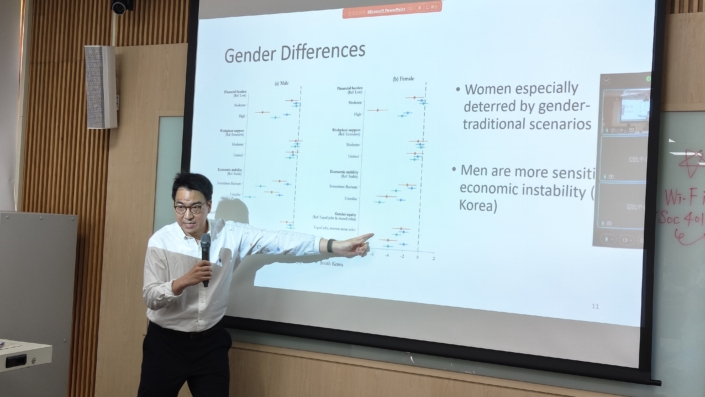

Structural Constraints and Relationship Quality in Marital Intentions

The second panel concentrated on changing marital intentions in Asia. Professor Sinn Won Han investigated the structural constraints influencing declining marriage intentions among young people in East Asia (China, Japan, and South Korea). He identified financial burdens and economic instability as the most significant inhibitory factors, with gender inequality having a notable negative impact on women’s marriage intentions. Chinese youth were susceptible to childcare costs, South Korean youth to future economic instability, and Japanese youth responded more moderately to various factors. Women were more affected by traditional gender divisions, leading to lower marriage intentions. Han emphasized that policies addressing economic insecurity and gender inequality could increase marriage intentions. Adam Ka-Lok Cheung analyzed conditional factors influencing marriage intentions among young people in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, finding that relationship quality had the most significant impact, followed by the full-time employment status of men. Poor relationships with future in-laws and co-residence with parents-in-law significantly reduced marriage intentions. At the same time, housing affordability had a weaker impact in Singapore, possibly due to government housing support. Cheung also found that women valued economic and relationship factors more than men, and that stronger individualistic values correlated with higher sensitivity to these factors. Professor Janet Chen-Lan Kuo explored changes in marital satisfaction among Taiwanese people, noting a general decline over the past decade, primarily due to decreased recognition of marriage as a source of happiness. Gender differences were evident: men’s declining satisfaction was influenced by increased marital duration, smaller age gaps with spouses, and lack of homeownership, while women’s decline was more tied to perceived unfairness in household division and increased marital conflict frequency, reflecting the highly gendered experience of marriage in Taiwan.

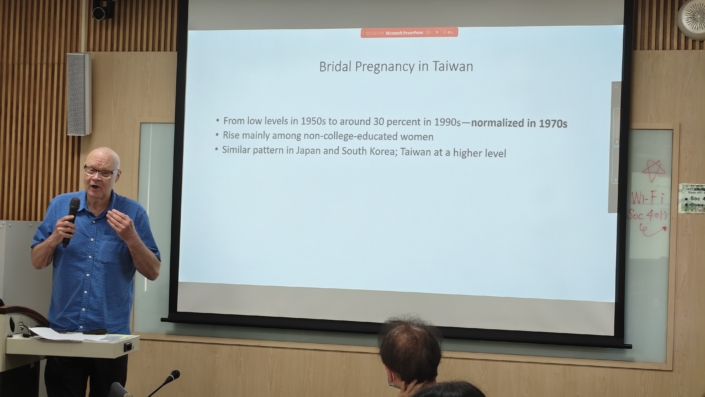

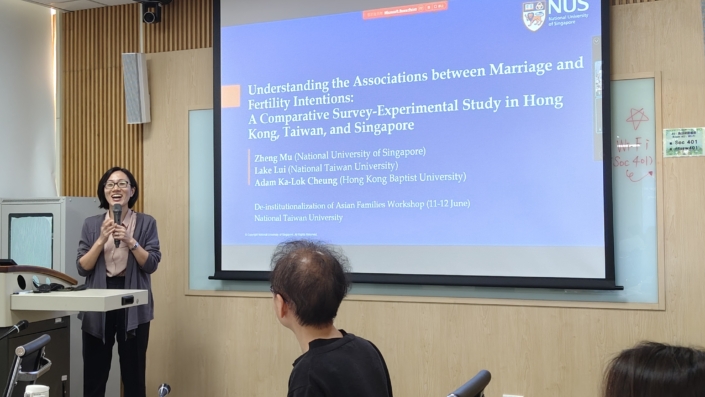

The Link Between Marriage and Fertility, and Alternative Family Forms

The third panel delved into the connection between marriage and fertility. William Lavely’s research on the rise of bridal pregnancy in Taiwan from 1940 to 1999 viewed it as a significant indicator of changing family norms during industrialization. The trend, especially among non-college-educated women, showed women using pregnancy as a strategy to advance marriage, indicating their increased agency in marriage and fertility. Professor Zheng Mu compared marriage and fertility intentions among young people in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. He found a general positive correlation between the two, but noted that individual values moderated this relationship. Those supporting familistic values closely linked marriage and fertility, while those endorsing gender equality and democratic values were more inclined to separate them. Women were also more likely than men to view marriage and fertility as independent choices. This divergence in views on marriage and fertility is increasingly evident across Asia, challenging traditional heterosexual norms.

The fourth panel shifted focus to evolving family-based care for the aging population and alternative family forms. Professor Chia Liu explored the high suicide rates among the elderly in East Asia (South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan), linking it to population aging and changing family structures that increase long-term care needs and pressure. She highlighted the exceptionally high suicide rate among older Korean men, especially divorced men, suggesting future research should integrate geographical and socioeconomic disparities. Professor Bussarawan Teerawichitchainan examined the prevalence and implications of male family caregivers for older adults in Thailand. While female caregivers still predominated, the proportion of male caregivers was rising. Despite this, older adults cared for by men reported significantly lower subjective well-being, possibly due to societal perceptions that men are less suited for delicate care. She recommended government-led training programs for male caregivers to improve care quality and promote greater gender inclusivity in caregiving roles.

The Stalled Gender Revolution and Reconfiguration of Asian Families

In the second keynote address, Professor Man-Yee Kan of the University of Oxford focused on the “stalled gender revolution,” using time as a central metric to examine how marriage and family institutions perpetuate gender inequality. She noted that despite advancements in women’s education and labor force participation, most countries remain in the first stage of the gender revolution, failing to challenge gender divisions within families truly. Her research showed that while women’s paid work hours increased, progress in East Asia (Japan and South Korea) remained limited. Gender differences in housework persisted, with women bearing most of the burden, and men’s increased involvement being minimal, especially in East Asian countries. Marriage and parenthood profoundly impacted time use: while men slightly increased time on housework in partnered contexts, women significantly reduced work hours and increased domestic responsibilities, a disparity particularly pronounced in East Asia. Kan concluded that marriage and family institutions remain central to reinforcing gender inequality, influencing women’s choices, and resource allocation. She called for welfare reforms and cultural shifts to facilitate the second stage of the gender revolution.

Determinants of Fertility and the Rise of Alternative Asian Families

The fifth panel further explored fertility determinants in an era of family change. Using South Korea as an example, Professor Paul Chang investigated how the quality of parental relationships influences children’s marital attitudes and family ideals, aiming to understand the ideological factors behind declining fertility and marriage rates. He found a significant positive correlation between good parent-child relationships and positive marriage inclinations in South Korea, notably stronger for men. He emphasized that relationship quality and psychological perceptions are crucial for understanding delayed marriage and fertility, urging policies beyond financial incentives to include family education and marriage counseling. Professor Yuying Tong focused on the increasing phenomenon of childlessness in Hong Kong, differentiating between voluntary, involuntary biological, and involuntary structural factors. She noted that highly educated women were more likely to remain childless as a lifestyle choice voluntarily. In contrast, lower-educated women, often influenced by traditional family values, might face involuntary childlessness due to economic pressure. She also found that rising housing prices significantly inhibited fertility intentions among highly educated locals.

The sixth panel showcased emerging alternative family forms in Asia. Professor Yue Qian examined the growing phenomenon of living-apart marriages in China. Unlike Western cases, often driven by voluntary choice, Chinese living-apart marriages are primarily driven by structural constraints like remote employment and children’s education arrangements. The proportion of such marriages rose significantly from 8% in 2006 to 21% in 2021. Individuals in living-apart marriages reported lower marital satisfaction and mutual disclosure, and higher loneliness and unhappiness. Qian highlighted this as a new normal driven by institutional and migration policies, reflecting the second demographic transition and diverging marital destinies. Francisca Lai’s research focused on the crucial role of pets in migration decisions and family reconfiguration during the post-2019 Hong Kong migration wave. Her findings revealed that pets influenced the feasibility of relocation and shaped the ethics of family care. For single individuals, childless couples, and non-heterosexual families, pets often became the core of the family. Lai advocated for including pets in the theoretical lens of transnational families and care ethics, rethinking migration policies and family definitions, and addressing the “sandwich care pressure” on middle-aged women caring for parents, children, and pets, which exposes significant gaps in institutional support for intimate relationships. Finally, Yen-hsin Alice Cheng portrayed the initial landscape of same-sex marriages in Taiwan after legalization. Her study, based on national marriage registration data, found that same-sex marriages constituted about 2% of total marriages, with a lower proportion of female same-sex first marriages. While the average age at marriage was similar to that of heterosexual couples, same-sex partners showed greater age disparities. Divorces within two years were significantly higher for same-sex couples (16% vs. 6%). The study also revealed higher “pairing heterogeneity” in education and age among same-sex couples, reflecting the novelty of the institution and limited pairing opportunities. Cheng noted that the characteristics of same-sex marriages reveal an intimate structure distinct from mainstream marriage, and their higher divorce rates and childlessness should be understood within the early historical and social context of legalization, prompting further attention to their intergenerational meaning and the development of support networks.

Transnational Intimacies and the Reconfiguration of Asian Families

In the third keynote address, Professor Wei-Jun Jean Yeung discussed the reconfiguration of Asian family systems amidst globalization and demographic changes. She proposed that Asian family institutions exhibit a co-existence of institutional weakening and re-strengthening, making it impossible to apply Western modernization or individualization theories. Despite delayed marriages, non-marriage, and sharp declines in fertility rates across East Asian countries, marriage remains an institutional gateway for family legitimacy in most Asian societies. Yeung invoked Harden’s (2024) three-dimensional framework of institutional forces—regulatory (legal policy), normative (social roles), and cultural-cognitive—to suggest that changes in Asian family institutions must be observed at these three levels, not solely based on individual behavior. She introduced the concept of “state-level institutional return,” where state apparatuses reaffirm the centrality of marriage through migration policies, marital regulations, and welfare design. Using Singapore’s SG-LEADS data, she analyzed the social integration of children with foreign mothers, showing how the mother’s language proficiency, social networks, and economic adaptation directly influenced children’s school performance. This reflects that family institutions are cultural products and tools of state governance and social exclusion.

Yeung emphasized that the institutional transformation of Asian families is not a singular path of “de-institutionalization.” While delayed marriage, non-marriage, and gender role reconfigurations challenge traditional institutions, these changes have not entirely replaced the institution of marriage as in Western societies. Instead, they are continuously reaffirmed through policy intervention and cultural reproduction. She argued that state policies play a central role by guiding individual choices towards marriage through welfare, subsidies, and social identity distribution mechanisms, making marriage a gateway to society and resources. Unlike the increasingly liberal views on marriage in the West, Asia exhibits a phenomenon of “marriage politicization.” Furthermore, Yeung believes that Asia needs to develop its theories of family change rather than directly apply modernization or individualization models. She highlighted that observing how non-typical families (such as foreign spouse families, LGBTQ+ partners, single-parent, and cohabiting families) encounter institutional boundaries and exclusion helps reveal how states define legitimate families through institutional means. These groups are often marginalized due to a lack of legal and welfare support, providing a crucial entry point for understanding institutional reproduction and social inequality. Finally, Yeung called for future family research to focus more on the interplay between institutions and culture, diverse family experiences and marginal situations, the impact of family changes on the next generation (e.g., education, integration, and social mobility), and how policies shape family choices and social stratification mechanisms. Families are not merely units of individual intimate life but also central sites of institutional operation and social exclusion, deserving of critical and localized theoretical exploration.

Written by Han Ji Chen, Chao-Kai Heu, translated by Hsiang-Yun Chang

-80x80.jpg)